Building Hope with Community

October 27, 2015

Fast-Tracked Project Threatens South LA Community

October 28, 2015Development in South LA: A Threat or an Opportunity?

"It will come as a surprise to absolutely no one that Los Angeles is in the grip of a housing affordability crisis."

Cynthia Strathmann PhD., SAJE Executive Director

Studies last year found Los Angeles to be the least affordable city in the country for renters. The average Los Angeles renter spends 47% of their paycheck on rent; to afford the average apartment a worker would have to make $33 an hour.

These facts are made even more meaningful if we consider that most people in LA — 52% percent — are renters, far fewer than in New York, a city long associated with a renting lifestyle. In parts of the city like South Los Angeles, that percentage is even higher; 77% of the people living just south of downtown are renters, a situation reflected in the dire housing predicaments of residents documented in the soon to be released study “Assessing Health and Equity Impacts of the Proposed Reef Development Project in South Central Los Angeles.”

South LA: Our Nation’s Most Crowded Neighborhood

Not only does South LA have an unusually large proportion of renters, but those renters are living in the most overcrowded neighborhoodin the entire United States. This is no shock when we consider that Los Angeles has both unusually high rents, unusually low incomes, and an unusually large number of people who are renting. Putting more people in one unit is an easy way to make housing more affordable, but with multiple families sharing small apartments, it comes at a cost in health and well-being. A 2012 study in Social Science Research noted that “In Los Angeles, there are clear and significant negative effects of crowding on all indicators of child wellbeing.”

Luxury Units Provide No Relief

The scarcity in housing affordable to ordinary people is, if anything, being made worse by the upsurge in luxury housing construction. Just across the 10 freeway from the overcrowded housing of South Los Angeles are a plethora of upmarket apartment buildings catering to newcomers who can afford the high prices. Those fancy new units aren’t relieving the pressure on housing any more than manufacturing Teslas would improve the market for used pick-up trucks; would-be pick up drivers don’t need a Tesla and they can’t afford one. In fact, recent studies in Atlanta show that increases in luxury housing development can occur simultaneously with pronounced decreases in the number of units affordable to lower income people. Given that most Angelenos are renters, there are real reasons, besides the standard carpings about design and changing neighborhoods, that building luxury housing is bad for us.

Ripple Effects of Development

Overcrowding isn’t the only unpleasant outcome of rising rents, the displacement of current residents is not far behind. When rents go up current residents may look for ways to stay in their old neighborhoods, which is one driver of overcrowding, but they can only hang on for so long, eventually people are forced to look for cheaper places to live. In Los Angeles this often means moving far away from familiar surroundings. This pattern has a number of pernicious effects. For one thing, it means that residents are disconnected from their social networks. Especially for the very poor, who rely on social networks as a bulwark against hard times and emergencies, this can be devastating for their physical security. In Los Angeles, it also means that low-income residents who rely on public transit may be forced to commute longer distances in cars to get to work. Without proper planning, high end development around transit can actually increase the amount of car travel because the regular riders who used to use transit are supplanted by wealthier residents who don’t. Finally, and most depressingly, a lack of affordable housing is one of the primary drivers of homelessness, and Los Angeles has seen a 12% rise in homelessness over the last two years. The effects of displacement don’t end with the inhabitants of a single home, they reverberate far out into the city.

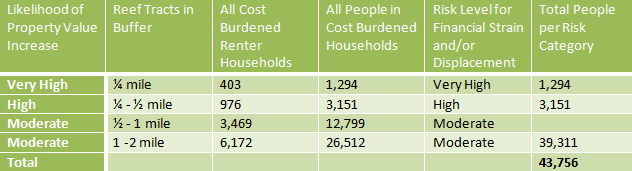

There’s a folk belief that the only development that leads to the displacement of people is new development that destroys existing housing in order to make way for new construction (A famous local example is the removal of residents from Chavez Ravine to make way for public housing in the 1950s; the housing was never built, and the site now holds Dodger Stadium). But given the way that rent increases ripple out from new developments this is hardly the only way that displacement happens. A recent study, set to be released October 26, of a proposed development in South Los Angeles estimates that almost thirteen hundred people are at a very high risk of being displaced by the development, and over 43,000 are at least a moderate risk of displacement. The proposed Reef Development, at Washington and Broadway, would have 1.7 million square feet of new development, including commercial, retail, restaurant, hotel, and grocery store space, along with 2733 off street parking spots. That mix will include close to fifteen hundred residential units; the total cost of the Reef development is estimated at three quarters of a billion dollars.

Figure 1: Rent-burdened households in proximity to the Reef Development*

*Source: Health Impact Assessment of the proposed Reef project: “Assessing Health and Equity Impacts of the Proposed Reef Development Project in South Central Los Angeles”

Opportunities for Change

Developments like the Reef offer the City, who controls the approval process for granting the large number of land use variances and permits developers need to realize their plans, to take a leadership role in ensuring community voices are heard and that development benefits the residents who already live in the area.

Much is made of the risks financiers take with their money, but they take risks with the health and well being of ordinary people who will see little of the potential profits available to investors. We need policies and land use planning practices that emphasize preserving and creating housing that is affordable for the majority of Angelenos. Without systematic interventions around developments like the Reef, Los Angeles runs the risk of becoming an island of wealth surrounded by a remote ring of destitution, exporting its poor to the hinterlands and along with them the vibrant diversity that comes with an economically integrated city as well as the promise of a truly inclusive society where everyone benefits from economic development.

*by Cynthia Strathmann PhD, Executive Director of SAJE (Strategic Actions for a Just Economy)